WELCOME TO YOP CITY

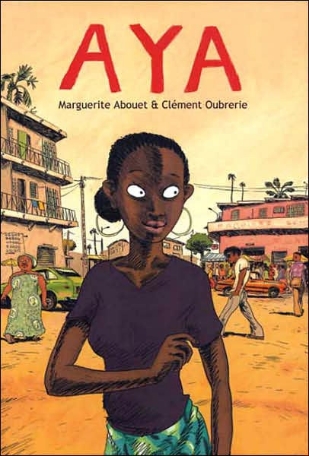

Aya, a graphic novel written by Marguerite Abouet and drawn by Clément Oubrerie, follows the comic adventures of the title character and her two best friends. They’re all young women who, despite living with their parents, manage to sneak out most nights to gossip, dance, and drink. Although, come to think of it, Aya doesn’t actually do any of those things. She alone holds dreams for the future—she wants to be a doctor—and so stands oddly aloof from the narrative hullabaloo surrounding an unexpected pregnancy. The action is funny and engrossing, but in the end has little to do with Aya.

In fact, the story is interesting primarily because it is set in late-1970s Ivory Coast. The publisher, Drawn & Quarterly, seems to understand this, which is why it has outfitted Aya with a preface by an academic. Alisia Grace Chase, Ph.D., dutifully fusses over the “vision of Africa in the American mind” and conjures images of starving children, machetes, etc. She also notes, but does not dwell on, the other central irony of the book (after its title). To wit: “The amorous hi-jinks narrated in Aya seem so familiar, so nearly suburban in their post-adolescent focus on dance floor flirtations, awkward first dates, and finding just the right dress for a friend’s wedding, that to many western readers it may be difficult to believe they take place in Africa.”

In other words, come for Conrad’s primitives, stay for the bourgeoisie.

It’s a bait and switch that works because Oubrerie’s drawings so beautifully capture both the setting and the tone of the book. If the setting is “so nearly suburban” that it could take place anywhere, the art is a constant reminder that Aya actually lives in Yopougon, a working class neighborhood of the nation’s capital. Aya explains that the locals call it “Yop City, like something out of an American movie,” which suggests that even the characters are a little confused about where they are. Are they in an American movie about dusty, working class Africa? Or are they in something more neatly suburban?

Oubrerie’s drawings are helpfully specific. An average streetscape gives us thatch on a roof, chickens on the road, clothes on the line, and the twist and color of a woman’s pagne skirt. A party scene, meanwhile, concentrates on groovy ’70s fashions, the high afro of the deejay, and the hovering skyline of the city. There are snatches of disco lyrics in the air and even a toddler dancing under the bar. (Where’d he come from?) And all of these images are washed in endless variations on brown and orange. They almost feel like a mirage.

As it happens, Dr. Chase uses that word to describe the relative prosperity of Côte d’Ivoire under its charismatic president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny. The strongman’s death in 1993 would initiate what these days is an all-too-familiar cycle: first the xenophobic politics, then the bloody coup, and finally civil war. Politics plays no explicit role in Aya, but the horror of what was to come lurks in the shadows nevertheless. Aya’s confession that she wants to be a doctor “to help people” comes off as a bit naïve, only to turn poignant in retrospect. Her father’s boss, meanwhile, is exactly the sort who would flourish in the future. His only interest is power, which means kissing up to the president and to the French, and demanding that Aya’s father kiss up to him.

This tension between past and future also helps to justify Abouet’s decision to add an “Ivorian Bonus” to the back of the book. The appendix contains a glossary of Ivorian references in the story, most of them bits of language liked “dêh,” an exclamation that intensifies meaning, as in “She’s beautiful, dêh!” Additionally, there is a section on how to wrap a pagne, how to roll a passaba, how to make a gnamankoudji, and how to prepare (and then hungrily consume) a Back and Forth. It’s clear that Abouet has a pressing concern that transcends the story: rescuing even a tiny bit of Ivorian culture from the recent madness.

Aya serves that worthy goal well enough. Indeed, it succeeds all the better for not being high-minded or didactic: Abouet allows the plot to skip across the surface of life, rarely setting down on anything more substantial than boy-meets-girl. Dr. Chase insists that Aya will not conform to our expectations of an African story. But for the starving children and machetes we need only wait for the sequel.

Aya by Marguerite Abouet & Clément Oubrerie (translated from the French by Helge Dascher) (Drawn & Quarterly, 106 pages)

Colorado Review, 2007