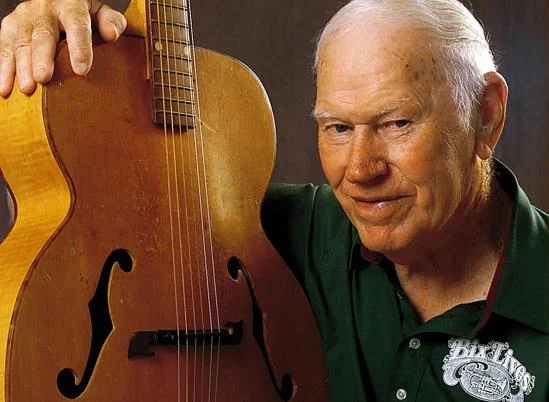

RICH JOHNSON AND LINDA MEADORS

Rich Johnson was the longtime musical director of the Bix Beiderbecke Memorial Jazz Festival in Davenport, Iowa and the author of Bix: A Davenport Album (2009). He died in 2008. Linda Meadors is the director of development for a healthcare company and a volunteer at First Presbyterian Church. I interviewed them on June 21, 2005, at the River Music Experience, a museum in Davenport.

[Before I turned the tape on, Mr. Johnson told me a story about going to the eye doctor and having someone notice the license plate on his car, which reads “BIX N ME.” The person asked him, “Oh, are you a runner?”]

[Talking about mixing more modern jazz music into the festival lineup]

RICH JOHNSON: It doesn’t mix. It’s like mixing kerosene and whatever. It doesn’t mix. I’ve been in concerts where they’ve had both. Don’t we have a right to listen to the music we want? You’d think we’d have a right. We are the dying breed, man. Last guy out, turn the light out isn’t that far away. I know ’cause I’m right up there.

BRENDAN WOLFE: When you say they want to change the music, who’s "they"?

RJ: Guys like Ridolfi [Mark Ridolfi, opinion editor of the Quad-City Times newspaper] and all these other people who write these nasty things about us. You know, there aren’t any black bands that play these types of music. They’ve moved on. Here’s something. Did you know there’s 70 other music festivals just like ours? Every one of those festivals are hiring the same bands we do. So, therefore, if we’re prejudiced, so are they.

LINDA MEADORS: But aren’t you dedicated to traditional jazz?

RJ: Sacramento is the largest traditional jazz festival in the world. Did you know they have a hundred thousand people out there? A hundred thousand people over a four-day festival. They’ve never had any problem with this. Neither has Denver. Nobody has. Just us. Just us, you know. Why? It’s the music. They want to change the music.

BW: Why do you think they want to change the music? Is it because they personally don’t like it?

RJ: They don’t like our music, which is fine. A lot of people don’t like our music.

LM: But why—I’m just asking this question—when they know that Bix is of a particular era, why are they—

RJ: They’re saying that if Bix had lived, he’d be playing this stuff. That’s like saying Rembrandt, what would he be doing? Would he be writing on the bathroom wall? God only knows what people do 50 years later. I mean, that’s ridiculous. So we want to play the music of the Twenties. And that’s what we do. We hire bands that play the music of the twenties. I turn down a lot of great bands. And I just politely say, “You don’t fit our music genre.” And they say thank you and move on. You know, it isn’t a big deal. When you’ve got people like that, I’m sorry, it’s sad. And I heard last year they were coming at us again. Jim Arpy, who’s worked 37 years at the paper [Quad-City Times], he told us that. If someone there asked me for an interview, I’d say I’ll give it to you, but it’s going to be in the publisher’s office with, we’re all going to be there together. I’m not going to have these lies again.

BW: So you feel especially threatened by the Quad-City Times? You feel that there’s something going on at the Times where they have an idea of what the festival should be.

RJ: I’m not saying the Times. I mean, they employ this guy. So I guess you’d have to say that.

BW: Mark Ridolfi?

RJ: Yes. He’s the editorial page editor and he sent this poor kid reporter out there. You can call Steve [Beiderbecke] up and ask him. He’ll tell you.

BW: He lives in Denver, you say?

RJ: Yeah. He was totally taken in by this. He didn’t know. A lot of the quotes in there that he supposedly said came from this reporter and the guy who sent him there. Jim Arpy wrote him right away, and Albert [Haim, proprietor of BixBeiderbecke.com] wrote him, and finally he let Albert write an editorial. Albert went through it line for line and tore him apart, which he can do.

BW: He’s very logical.

RJ: Yeah. He and Jean Pierre [Lion] were great friends until Albert reviewed his book.

BW: I saw that. And now they don’t speak.

RJ: Yeah. And it was strictly because Albert wants facts. And Jean Pierre said the reason Bix drank was because of this. And that don’t go over well with Albert. He wants facts.

BW: Well, that’s a problem. When you a tell a story, a story is not just a string of facts. A story is more than that. A story is lots of whys and hows in there. And everyone can take five different facts and tell a different story. And I guess you can have differing opinions on whether a biography should be a string of facts, which is like Phil Evans and Linda Evans’s book. It’s a remarkable thing. I’ve never seen anything like it in my whole life. But it’s not a story. It’s facts. And it’s different people’s recollections and it’s really interesting. And it’s such an amazing resource. And Jean Pierre’s book is not that.

RJ: The first book, Bix: Man and Legend—Evans hated that book because he gave Sudhalter the facts and Sudhalter reneged on a few of them. So he called him “Suds-Duds.” He hated him. When he published this book [The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story], it was to correct all the errors. Everything he said in there, he had a backup for: a phone call, a conversation, things like that. And I’ll tell you another story. We worked together, and they had it all set. It would be published. And he called me up crying about a month before the festival. He said the publisher in New York had called him and told him the deal had fallen apart. He said, “Do you know anybody in Davenport?” I said, “Man, I don’t know nothin’.” So I said, “I’ll see what I can do.” So I went out and found, I don’t even remember who it was, out in northern Davenport. And I went to him and I says, “Here’s the situation. This company has all the disks and everything. If I can get that to you, can you publish it and have it ready by the festival?” And he said, “We’ll see what we can do.” So that’s what happened. I met Evans at the airport holding his book up. He’d never seen it. That’s a true story.

LM: So his book was actually published in Davenport?

RJ: That’s right. It doesn’t say that on the book, but it was. We sell them. But it’s very difficult to read. You have to be a Bix aficionado. Bix: Man and Legend was well-written. Sudhalter did make it readable. One of the things about Phil and Linda, they named it The Leon Bix Beiderbecke Story. Well, his name wasn’t Bix. It was Bismark. And I have so much proof it’s unbelievable.

BW: It’s amazing how people can’t even decide or agree on what his name is!

RJ: I have the Tyler School records where it’s Bismark. But the best proof of all, Mary Hill, who was Agatha’s, Bix’s mother’s, aunt and who raised her with Carolyn, Agatha’s mother, died—Mary raised her, and a lot of people don’t know this because it’s wrong in the book, but when Bismark and Agatha got married, they didn’t move into their new house at 1934 Grand. They moved in with Mary Hill. In fact, Burnie was born there. And the house is still there. So they didn’t move in there till later. Later on, Mary went and lived with them. When Mary died, the four people in her will were Agatha—Bismark had died—Agatha, Mary Louise, Burnie, and Bix. And they all signed the will. But Bix was underage, so his mother signed. And what do you think she wrote? Leon Bismark Beiderbecke. If that isn’t proof, I don’t know what is! But Phil and Linda to this day swear up and down that his name was Bix.

BW: What about his birth certificate? That says Bix doesn’t it?

RJ: You know what happened? It was altered. I have those records. It was altered in the Fifties. His birth certificate was altered. It was “Leon B.” but they altered it to “Leon Bix.” Burnie did it. Why, I don’t know. So, if you look on the birth certificate, it says “Leon Bix.”

[Mr. Johnson talks about some of his research, tracing the history of the guy who flunked Bix in his union audition, for instance.]

BW: Why is it important that people know about Bix? Or is it important?

RJ: First of all, if you type in "Bix Beiderbecke," you get 30,000 sites. Now type in "the mayor of Davenport." Or "Figge," or somebody else. He’s the best-known guy worldwide of anybody here. Whether you like it or not, he is. He played at Carnegie Hall. How many guys do you know that played at Carnegie Hall? He’s got a lot going for him. The thing that isn’t going for him is that the guy was an alcoholic. And that’s bad, you know. If somebody walked in here today and said, “I just found a cure for cancer, but I’m an alcoholic,” they’d say, “Get the heck out of here. We don’t want anything to do with you.” It’s almost that bad. As a musician, I know. I’ve seen a lot of guys go down the drain. It was the era, too, Prohibition, the Roaring Twenties, and unfortunately it killed him at 28 years old.

BW: Do you think Bix’s alcoholism affects how Davenport remembers him?

RJ: Yeah, I do.

LM: Well, I speak from a little different perspective. Bix is part of Davenport’s history. And we’re in Davenport right now. And we’re part of Davenport’s history. And what appealed to me when I connected with Rich about eight years ago—there are certain facts. Bix did live. Jazz in the 1920s has impacted people around the world and we just happen to be in a key location. And Bix was here. And all the conditions were right in the Twenties for him to do what he’s done and leave us the legacy. And that’s facts. I love the festival, the music has spoken to me. I have had to acquire that, because I was raised in a generation where my parents did not introduce me to that form of music even though they had probably been raised with it. So I was kind of an outsider coming in to this and have had to do some of my Bix homework. But to me the fact remained that he was from Davenport, I happened to go to the church where his mother was organist, his family was here. I wanted to know more, and I frankly thought that if I as a newcomer wanted to know more, I thought that others would, too. So the way I approached it was, I went to the best source. I connected with Rich to basically say, Why hasn’t the church and the Bix Society done something? Then we had to sort through a little bit of history. But I guess I’ve found it’s communication, it’s how we as a church today tell the story and show our pride when we call ourselves now Bix’s Home Church. And in fact if you drive down Kirkwood, we have a sign that’s right on Kirkwood Boulevard, and we usually put it out about July 1 with a big picture of Bix: “Bix’s Home, Too.” So I’ve found that over the years, what we think about is what are we doing today to perpetuate his memory? So I look at it from a much more positive perspective. And over the years we have pulled in more and more volunteers. We have more people from our congregation telling others, You’ve got to come to our church, you’ve got to come Bix Sunday. Wonderful, positive things happen. And the very first year that Sue Howes decided to do a sermon about Bix—

BW: When was that?

LM: That would have been probably 1997. This was not when we were the official liturgy. It was just us doing it with a local band, and we had not partnered. And what I found really interesting was that Rev. Howes, she just shared her own family situation. She had a relative who had alcoholism, and she shared it. She brought up how families need to support family members when they’re having difficult times. She spoke from a personal experience because people will talk about alcoholism, and alcoholism with musicians, and alcoholism during the Roaring Twenties. She didn’t just zero in on this young man like he had the only problem in the whole world. What she was addressing was that this is something that families have had to deal with for centuries. But the fact that she was willing to talk about it at a worship service, and people were able to talk about how things really haven’t changed. Things that were problems in the 1890s and the 1920s are still problems. But what I’ve found was that she was fascinated with history. She was fascinated, I was fascinated. We connected with the Bix Society. And there were things that Rich wanted to know, information that the church had. So first we had to partner with people who care and who also want to teach some of the stories, some of the truth and legacy. But we also wanted to celebrate, to allow a worship service to show all of the positive things that music and a caring community and a caring family can do.

RJ: You’ve done a wonderful job, and it’s hard to get into any of the services.

BW: So the response from the church community and the community beyond the church has been really positive?

RJ: Getting back to Bix, I realize, first of all, people don’t like history. They don’t, you know? I’m a World War II veteran.

BW: In Europe or the Pacific?

RJ: Pacific. I spent two and a half years in the Pacific. I was wounded, my brother was killed. We had a reunion a few weeks ago. You know how many showed up? Seven.

BW: What branch were you?

RJ: In the infantry. World War II today is nothing more than an R-rated movie. And that’s the truth. Unfortunately. But that’s the way that people are. They’re not interested in going back. So I don’t expect people to be interested in Bix. Don’t you agree? And we’re going to be dead. We’re going to be dead here in a few more years.

LM: But you have to package it a little bit different. I mean, if we called this the Bix History from 8:30 to 9:30 on Sunday mornings, who would come? But instead, we’ve tried to get a lot of youth involved, and they’re dancing to music of the Twenties, and we’ve got this great jazz band, and we pull our choir in, which has got 75 voices. They’re having a ball. They’re just having a ball with this. Bix is touching them. But I think he’s touching them on their terms. The whole family is coming to the Bix liturgy because maybe that teenage kid is dancing to the music, or that it’s a choir member or my mom or my dad is in that choir. But we’re there at the Bix liturgy. And something that our pastor last year did, it was called “Bringing Out the Best.” Bix was able to bring out the best of his talents when he was performing, or at Carnegie Hall, or when he was composing “In a Mist,” and that’s what we need to be remembering , bringing out the best. So you can do a fifteen-minute message on bringing out the best on a Bix Sunday and pull out examples of Bix’s life, you could pull examples out of your life, you could pull examples out of anybody’s life, except on that weekend people are focused on Bix. And so you’re still feeding them a little bit of history. Our church, we’ve really cherished the partnership we’ve had with the Society. We meet jointly and discuss the sermon. These are the points [the pastor] wants to highlight. And then he asks Rich for research.

RJ: Yeah, he really did a good job.

LM: Because it’s a point of pride. I guess I just want to make it a positive experience and celebrate the fact that we’re from Davenport, Bix was raised here, and we have the only Bix festival that really means anything.

BW: The facts aren’t always what people are connecting to. Facts in service to a story are what people sometimes connect to. How do we look at those facts in terms of what they may or may not mean? How important is Bix’s life as a story we tell about Davenport?

LM: Well, he has become a legend. And I think that’s the thing about any legend, or any biblical character. He was one of our most famous sons.

RJ: He is, but he won’t ever be recognized by anyone else here but us.

BW: Do you think Davenport’s going to forget him?

RJ: Yeah. And I really believe that. We’re fighting a losing battle. The festival is going down one of these days, just like the rest of them. It’s a generation thing. And I wish that young people could catch on to it. I mean, I was the same way. But today’s music isn’t even music. I don’t understand it at all. There’s no music to it.

BW: It’s ironic that Italians, the Avati brothers, introduced me to Bix Beiderbecke. He’s very big all over the world.

RJ: All over the world except here. Spiegel Willcox used to come here. He came here till he was 96. And he told me, “Rich, they think I’m god in Europe because I played with Bix.” And you know, jazz is our only natural resource. Everything else came from other cultures. But jazz came from here. It’s the only thing we can claim. Bix is remembered all over, but I can understand that the music doesn’t fit the people living here unless you’re 80 or over. And, you know, I’m not mad at anybody. I’m mad at the guys who try to attack me for no reason at all. That’s what I’m mad at. I’m not mad at the runners. We let them in free if they have their badge on. We figure if they buy a bottle of beer, they’ll like the music. There’s no quarrel there. And I like Ed Froelich [director of the Bix 7 road race].

BW: What about the whole Elvis thing?

RJ: Bix means nothing to them to begin with. If you look at their 20-year report, or their 25-year, whatever, there’s not a mention of Bix Beiderbecke in there. They’ve got as much right to the name as anybody. A few years ago somebody tried to come here and sue us for using the name. It wasn’t the family, either, it was somebody else. They said they had it copyrighted and everything.

BW: Not connected to the race.

RJ: No, no. It was just some guy out trying to make a buck.

LM: The jazz festival is older than the race, correct?

RJ: Oh, yeah. When we started it, there was nothing here. There wasn’t a Bix downtown, there wasn’t anything. And we started it with some help from Davenport. Actually, it was started by the guys in New Jersey who came here for a pilgrimage. That’s what started it. They tried to start it here years ago, but it never took off. But it was just that one spark that got it here. When they had that jam session out there at the Holiday Inn, they had so many people, they couldn’t get them in.

BW: How has the festival changed Davenport? Do you feel like it has?

LM: I just think it has impacted the community positively, and then when you add in all the other things, like the blues festival, the hotels, the tourism dollars. I guess I can’t think of a business that is complaining that we have a Bix Fest.

BW: Just the word Bix is a huge part of Davenport’s civic identity, and maybe it wouldn’t be that way if there hadn’t been a festival.

LM: I agree.

BW: Maybe there would have been a race without the festival, but it wouldn’t have been called the Bix 7 race. And maybe that name and that image and that story wouldn’t have been there to tie all these events and this community together.

LM: Every year I see the ripple effect of more and more people being touched by the whole weekend. Last year when Vanderveer Park was celebrating the opening of their big fountain, they approached the Bix Society and asked if there could be a band there for a two-hour period. People brought their lawn chairs, kids were playing all over, and they were celebrating this rededication, and there was the Bix presence. Down in Middle Park in Bettendorf we’re seeing that. The last two or three years they’ve had these hundred trumpets. You’re getting high-schoolers, you’re getting young kids. They’re excited because there’s a hundred trumpets, and they’re down in LeClaire Park, and it’s because of the name Bix, that weekend. It just generates creativity, and I just think an awful lot of good is happening along the way. At the church, beyond the Bix liturgy, I have tried to do some educational things so that people understand a little more of the history above and beyond what they hear on that one Sunday. Rich and I have put together an information session that we call “Puttin’ on the Bix.” We let people come and they would see the documentary. Then we would even show videos of previous year’s liturgies. And then last year, I guess we felt we didn’t really have anything new. We’d done it three years, and we’d shown the documentary and such. So last year we stole an idea from the Bix Society. We wanted to do a Bix trolley tour. But not do it during the festival because there’s too much going on and we didn’t want to compete. So we did it a couple of weeks before the festival. And Rich got on one of the trolleys. He was a tour guide on one of the trolleys, and one of our church members got trained by Rich and she was on another trolley.

BW: Where do these trolleys come from?

LM: We reserve them from MetroLink, which is the actual public transportation company in Rock Island. We rented them for the evening. Rich put together the information for the script. And then the other thing we did, we contacted Marlene at the Beiderbecke house, and she gave a tour of the house. She was doing it because the church was sponsoring it and she was partnering with us. And then Pam DeRouque of the Beiderbecke Inn wanted to partner with us. So we were able to take the 40 of us, two different trolleys, so twenty each time and go into the Beiderbecke Inn. She shared the history she knew, showed us as much as the public space as she could without interrupting her guests, and then served a delightful strawberry shortcake. So that people were able to sit in that dining room, the same dining room that probably Bix sat in at times with his parents, so we were just soaking in that history, but in a real subtle way. Our congregation loved it, and we’re doing it again this year.

BW: The grandparents’ home is the B and B. Tell me about the parents’ home. Who owns that?

RJ: The Avati brothers that made the movie. They own it as an office. And Marlene McCandless is the secretary, and she’s there every morning from nine to twelve during the week. And if you talk nice to her and tell her you know me, she might take you on the tour.

LM: You know, the church has a certain credibility. When we ask on the behalf of the congregation—it’s open to the public, too—then we are able to offer some things that maybe somebody else couldn’t offer. And that’s what I’m always looking for, to enhance things a little.

BW: Tell me about the relationship between Davenport, the festival, and the Avati brothers.

RJ: The Avati brothers are strictly on their own. They maintain that office. They’re supposed to be coming over here soon to make another movie. They do that. They had Brooke Shields in one here. That’s the only connection there.

BW: What did you think of the movie?

RJ: I didn’t like it. It was strictly Hollywood. Bix went to Lake Forest, and guess who his roommate was? Hoagy Carmichael. He never went there. He went to Indiana University. You know, why not make it halfway decent instead of making up stuff? And the movie didn’t have much music in it. It was mostly that he was drunk. And he came home drunk for his sister’s wedding, which didn’t happen.

BW: The wedding didn’t happen?

RJ: No. He came home. He was in the wedding party. He wasn’t drunk. They had him coming home and spoiling the party. I said to Pupi when he got here, I said, “I’d like to help you write the script.” He said, “We wrote it in Italy.” I thought the local people did a good job, the local actors. I thought they were able to create the era real well. I thought the antique cars, the rocks on the streets, the music was great. Pupi gave me a free ticket to the opening, and afterwards I told him what I thought, and he said, “You gotta remember, it’s an interpretation.”

BW: It’s right there in the title. Is he a nice guy?

RJ: Yeah. He’s a very nice guy. He plays clarinet. He’s a jazz clarinet player.

BW: I remember getting yelled at a lot.

RJ: Were you in that scene at St. Ambrose [University]?

BW: No.

RJ: They dropped it out of there. I went over to see him. He directed that scene. It was a scene in Lake Forest where Bix was just coming home and they were all doing exercises. And Bix comes around, and he’d been out all night, and Pupi stood there directing him with his arm around me. And then they took it out of the movie. They cut out twenty minutes of the movie in its final form. But I got the original.

BW: Here, we talk a bit about the financing of the festival and in particular an article in the River Cities Reader.

RJ: We’re a sincere bunch of people. We work our butt off. People don’t understand, if it weren’t for Mary Ellen giving us money ever year, we would be gone.

BW: Who’s Mary Ellen?

RJ: Chamberlain.

LM: The River Boat Authority. The gambling boat money.

RJ: They give us money every year.

BW: To the Bix Society.

RJ: She gives it to anybody, everybody, you know. We’ve been lucky to get it the last few years. She helps us out. I’ll tell you, Neil Birdsell, our president, about seven years ago mortgaged his house to keep the festival going. That’s what I call dedication. That’s the kind of shape we’re in financially. We don’t make it on attendance. If we didn’t have sponsors we’d never make it.

BW: What in particular was wrong with the Reader article?

RJ: Well, for one thing, they let Jimmy Jones write it. He’s a friend. He’s just a little warped. He’s married to a black woman, so he isn’t just prejudiced, he’s super prejudiced against whites. Super prejudiced. So he’s not a Bix fan. He’s the other way, which is fine. He’s written some things about us. He doesn’t understand. He’s recommend some bands for me to hire that don’t even play the same style of music. See that’s the problem. In the political campaign it was, “It’s the economy, stupid.” Well, in our case, “It’s the music, stupid.” If you don’t understand the music, well, I can see where they’d say, Why don’t you hire this band? But they’re not playing the same kind of music! It’s different music. Why don’t they just leave it alone.

BW: Do you think the festival will ever come to point where it’ll say, hey, we’ll have some music that Bix would have played, but we’ll have some other music that will attract some young people? And we’re going to do it all in honor of Bix.

RJ: No. And I’ll tell you why. If you had a lot of different venues and just segregated that music in there, it would probably work. We don’t have that many venues, and I just can’t see us doing that.

LM: But in a way, there’s a street festival, at least on Friday night and Saturday, they are keeping young people downtown with that fest. For all we know, in fact, I can say this, I would be down at our Bix Fest, but my kids like to be up here with the vendors and the music here, so we’re both downtown in Davenport. So I think that the street fest has picked up on that type of approach.

RJ: But they also hire jazz bands to play right against us, which is not in the good neighbor policy. I can see if they got blues or they got zydeco.