LOUDER THAN THE BOMBS

Too often, we Americans undergo experiences of a dizzying complexity only to dismiss them in language that is evasive and simplistic (Watergate to Monica-gate, Westward Expansion to Decision 2000). And Vietnam is hardly an exception: a mere three syllables—as a long line of scholars will attest to, have solemnly attested to—referring not to a basket-shaped peninsula jutting into the South China Sea but to a momentarily exposed tip of the American subconscious, more or less neatly tucked away again when George Bush gleefully announced the end of the Vietnam Syndrome in 1991. In fact, as Pacific News Service commentator and Vietnamese-American Andrew Lam recently observed, the war was “a difficult narrative that often gets reduced to two sides – America versus all Vietnamese.”

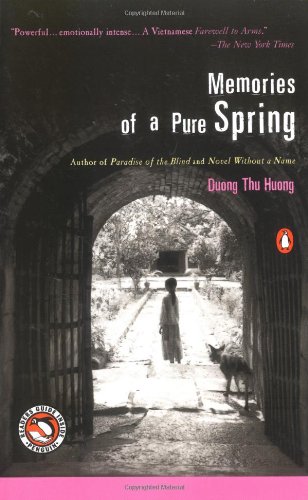

Which may suggest one of the values of a novel like Memories of a Pure Spring, published in January and Vietnamese dissident Duong Thu Huong’s third to be translated into English. After all, there has not been any great flood of literature to come crashing out of the Communist nation in the last 30 years (Bao Ninh’s now-class The Sorrow of War is a wonderful anomaly or, more recently, Ho Anh Thai’s short story collection Behind the Red Mist). Instead, our attention has been focused on curiously homegrown fiction like Robert Olen Butler’s short story collection A Good Scent From a Strange Mountain, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1993, and also which, according to a blurb on the cover of its Penguin paperback edition, “caught for us the Vietnamese sense of elegance and delicacy, history and family.”

In other words, one is tempted to burden Huong, who is actually Vietnamese, with explaining her people to Americans, with debunking even the liberal perspective—as Lam puts it—of “Americans as perpetrators of violence and Vietnamese as innocents in conical hats, waiting to be murdered.”

Happily, Huong ignores any such pressure. She’s the real McCoy, it’s true, who presumably has worn a conical hat or two and who led an artistic troupe and youth brigade in the North Vietnamese Army. According to translator Nina McPherson, after having spent ten years in the tunnels with her group of forty, “singing louder than the bombs.” Huong emerged one of only three survivors. She joined the Communist Party and wrote spectacularly popular novels until 1989, when the Party rebuked her for her criticism of land reform in Paradise of the Blind. Her work was quickly banned, and, in 1991, after smuggling out of the country her manuscript forNovel Without a Name, she was jailed for seven months without trial. Remarkably, Huong remains in Hanoi, where she continues to write, her legend broadening and thickening, so that in some Western circles she has become a kind of literary John McCain.

It is precisely because of this biography, however, that Huong is able to use her novels to speak to Vietnamese. For example, as Novel Without a Name lurches toward its unhappy conclusion, its soldier-protagonist Quan is visited by a war-weary ancestor who dramatically announces, “History is enmired in crime.” This is important news for Quan, who, like all good Buddhists, worships at the altar of his ancestors and who, like all good NVA, uses past, heroic victories to justify his current suffering. “In my time,” complains the ghost,

we killed each other with sabers and lances. A letter took a week to reach its destination. Humanity was fragmented, cloistered in small savage warrens. We lived in ignorance, isolated, like wild beasts, incapable of seeing over the bamboo hedgerow ringed with thorns. There was no promised land.

Far from intending this as an excuse for Quan to quit the fight, the ancestor informs his progeny that “however many generations it has been, you belong to me.” You owe me. “Don’t betray me.” Angrily, sadly, guiltily, Quan responds with the jungle equivalent of the finger – a triumphant, if also tragic, moment for a Vietnamese enmired in the maddening circularity of his own difficult narrative, unable to so blithely dismiss history or march beyond it as his American enemy. Meanwhile, the distilled force of the author’s own experiences resonates in the scene’s pain, helping to transform a mere assault on ideology into a bristling personal revelation.

Such a moment also perfectly sets up the irony in the title of Huong’s latest novel,Memories of a Pure Spring. It is the clearly autobiographical love story of a composer, Hung, and his devoted but much-younger wife, Suong, both veterans of a front-line cultural unit and now desperate to find some personal, political and professional stability in post-war Vietnam. They cannot. Hung falls into the bottle and out of favor with local Party officials, until he is eventually imprisoned. Sung, otherwise successful, responds by attempting to drown herself. (Huong, meanwhile, inflicts deliciously black irony on poor Hung. Arrested for fleeing the coast with boat people, he had only joined the group after being threatened. He had run away from his domestic troubles, you see, and passed out drunk beneath a pile of fishing nets. When the boat people found him, they kidnapped him as insurance on his silence.)

After his release –secured by Suong, who uncomfortably uses her fame as a singer and her wiles as a woman on the camp warden—Hung drifts. In the space of only a few pages, he witnesses “a rain that crushed the land, reduced gardens to mud, that churned and swelled the rivers,” only to then find “enchanting,” “unbridled” freedom in the water of the sea: “He discovered the sea: the free unbridled sea that belonged to no one, that answered to no one, that was no one’s slave. Mesmerized, he gazed into the vast expanse of the water as if he too could vanish into its endless churning.”

For Hung, though, these sorts of epiphanies are too little, too late. Such optimism, after all, might have helped prevent an ever-more-miserable Suong from being caught in the “endless churning.” What they do accomplish is to turn his face away from family and inexorably toward his art, a similar turn made by Quan in Novel Without a Name, when he spat back at the ghost, “I don’t give a damn about your triumphal arches, or you. Stop bothering me. I’ve had enough.” Hung doesn’t have the tongue for such a declaration; instead, he moves in with a small group of poets and painters, until he washes up almost dead in an remote opium den.

Memories of a Pure Spring is a novel that, like Vietnam itself, twists and churns, backtracks and races forward, while always turning the screws on its characters with both authority and anguish. Nowhere is this more the case than in the climactic eleventh chapter, wherein Hung, who has gone missing from home, engages in stuporous debate with his miscreant friends. Again, it is water—or rather “plantain leaves, shaken by the rain, shuddered, bending and rising, infinitely patient, resisting the downpour”—that triggers in Hung some kind of release, pathetic as it is courageous: “You can only create art when you live with dignity, in a free society,” he says. “Even a slave knows how to put pen to paper, or mix colors on a palette. But a cowardly, servile, hypocritical soul can never create art.”

Hung’s colleague Doan then questions him as if he were a trial witness, provoking frustrated laughter, until it is revealed that their conversation has been secretly recorded. It is one final, unbearably cruel irony for Hung. On the lam from his loved ones, hiding from a watchful government, wracked by drugs, alcohol and self-doubt, he is able just this once to “sing louder than the bombs.” So when Doan runs for it, there is “rain, still rain. Water and more water, white sheets of it, as far as the eye could see. In a flash, Doan had disappeared.”

If sometimes Huong’s shimmering prose also stumbles up against grandiosity, so too her characters stumble up against the grandiosity of their ambition, of their memories—however insincere—and of their geography, and for them (and the reader, too) the fall is both long and beautiful.

Memories of a Pure Spring by Duong Thu Huong (Hyperion, 356 pages)

Iowa Review Online, 2000