FINDING HIS INNER REDNECK

William Carpenter isn’t the sort to load up his .30-30 of a Sunday and discharge his frustrations into a few helpless seals. There’s no evidence he cheats on his wife or would beat a girlfriend. And in the presence of this reporter, anyway, he has never employed such epithets as “Krauts,” “fairies,” or “slant-eyes.” In fact, the Stockton Springs writer admits he is practically 100 percent the opposite of Lucas “Lucky” Lunt, the hard-swearing, pill-popping Maine lobsterman at the Havoline-fueled heart of The Wooden Nickel, Carpenter’s just-released second novel.

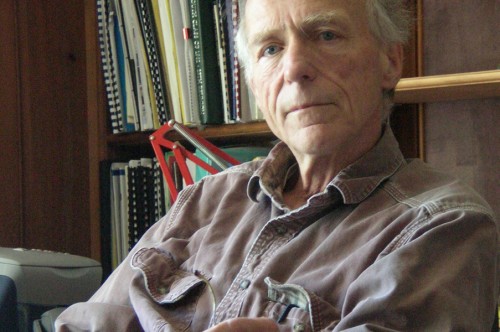

“To be human beings, we have to accept everyone,” argues the anti-Lunt, a 61-year-old optimist with steely blue eyes and barbed-wire eyebrows. He leans forward in his rocking chair while paintings and sculpture loll about in the sunny, open front room of the former inn he shares with wife Donna Gold and their son Daniel. “In these days of political correctness, the middle class tend to reject much of humanity and draw a circle around their own experience,” he says. “I hope, after reading this book, they will have expanded their circle of sympathy.”

It’s an intriguing and perhaps even admirable goal for a novel—getting in touch, as Carpenter puts it, with his inner redneck. Inhabiting a “pirate consciousness,” he pushes Lucky up against the limits of any civilized reader’s patience and then, amid choppy seas and on the back of one disgruntled, all-too-mythic whale, attempts to redeem him.

But does it work?

Wouldn’t it be a trick if it did. Even Maine’s hardest-bitten class-warriors—novelists like the gun-toting Carolyn Chute, Sandy Phippen down in rural Hancock, and Richard Russo, whose Camden address belies his more modest upbringing—avoid straying too far from their own kind. And that was Carpenter’s instinct, too. When he first sat down to write a novel of the Maine coast, this son of an art professor, who for 30 years has taught English at Bar Harbor’s College of the Atlantic, created and cast aside a couple of different, educated protagonists. There was the college teacher dropout, fired after being charged with sexual harassment, who ends up working on the docks. “A hopeless cliché,” Carpenter moans. Then there was the ex-lawyer and boatyard owner, a guy who witnesses a lobsterman shooting seals and predictably turns irate.

“I was stuck,” Carpenter confesses. “I had a picture of someone like me, a middle-class person coming to Maine, sitting up there on his porch drinking gin and tonics. The problem is, I wanted to be down with the lobsterman shooting seals.

“So one day I was out sailing with a friend,” Carpenter continues. “We were eating our al fresco breakfasts. I’m sure we looked like the privileged classes, two sailboats side by side, when suddenly this sizeable, heavy-displacement lobster boat took aim at us and came in way too close. He completely destroyed our breakfast. We were furious. It was so deliberate, so mean. I began to write a week later.”

Out of that turbulent wake was born one Lucky Lunt.

“Every one of them things is some son of a bitch screwing the working man,” Lucky grumbles early on in The Wooden Nickel, when he spies the likes of Carpenter out on the water.

Then he slows down, edges a point to starboard so he can see behind the canvas dodger and there they are, five or six of them in the cockpit not doing a god damn thing, getting drunk while the money comes gushing down the mast from the satellite. Look at the bloodsuckers, three in the afternoon, swilling martinis like a bilge pump. Come suppertime they’ll reach over and pull up some poor lobsterman’s trap and steal a day’s catch, living off the labor of others, worse parasites than a colony of fucking seals. “Sons of a whore,” Lucky yells and heads right toward them, turning the throttle to 2200 rpm.

LUCKY AGAINST THE WORLD

The Wooden Nickel follows Lucky from the before-dawn beginning of one lobster season to its bitter, underwater end, months later. One of the joys and failures of the novel is Lucky’s sheer outrageousness. At 46, this Vietnam vet and blustering resident of fictional Orphan Point is at war with tourists, with his artist wife and rebellious kids, with his miserly buyer (whose estranged wife Ronette he takes on as his stern man and quickly impregnates), and with his fellow lobstermen. Shots are fired. The aptly christened Wooden Nickel catches fire. His chronically unhealthy heart “flops like a mackerel.” To calm himself, Lucky turns to country music and the bottomless joys of the internal combustion engine: “He can feel in his own circulation the Havoline 10-40 gushing from the pump to lube the pistons stroking in and out of their cylinders like a tight-holed fuck, the nervous gossipy valves jumping in their seats, the crankshaft in its warm surrounding oil like the vertebrae of a spine.”

Virtuoso moments like these are the literary equivalent of Henry Miller pulling up beside Bruce Springsteen at a stoplight, engines revving, tires squealing. What could be more fun?

There are times, though, when Lucky’s character, while struggling to maintain his family’s fishing tradition in a new world economy, still seems to amount to little more than a series of humorous quirks and xenophobic rants. He has the tattoo of a Marine troop carrier on his chest. He compares Asian-made cars to Pearl Harbor kamikazes, “only this time the suicide pilots are us.” At his daughter’s high school graduation, he mistakenly concludes that the AIDS ribbons she and her classmates wear indicate infection. No, Moby Dick was not the whale, he insists, but “this one-legged skipper out of New Bedford, he killed so many whales the government shut down the fishery.”

Is Carpenter making fun of Lucky? That wouldn’t be such a problem—this could be called parody, after all—if the author, like his rejected protagonist, weren’t sitting up there on his porch. From such a vantage point, parody can veer too close to smug judgment, and this is precisely what The Wooden Nickel seems otherwise designed to avoid.

Lucky isn’t the only character Carpenter stacks the deck against. Turns out that the sailboat Lucky buzzed belongs to his au pair daughter’s rich employers, an unexpected fact he is forced to digest over dinner with the couple. Dr. Hummerman relates how some lobster boat came “quite out of nowhere,” and after detailing the damage, he innocently concludes: “I honestly thought the poor fisherman had died at the helm.”

If, as a victim of the same crime, Carpenter was “furious,” then why doesn’t he allow his fictional character the same honest reaction?

Part of the problem has to do with point of view. The Wooden Nickel stubbornly parks itself inside Lucky’s bait-smelling, truck-obsessed head at the expense of any other perspective. Carpenter says the technique was a deliberate attempt to move beyond his poetry, which focused, he says, on “the analogs of my own life.” Carpenter is the author of three volumes of verse, including Rain, which won the national Morse Poetry Prize in 1985.

“My goal is to completely annihilate the presence of another consciousness,” he explains. “In my opinion, most books have an overbearing narrative presence. It’s like the author feels like he needs to constantly interpret the book for you, like he needs to hold your hand.”

No such hand-holding in The Wooden Nickel, and often the strategy works. Midway through the novel, Lucky observes: “Whale’s just another homeless fisherman, looking out for himself like anybody else.” And sure enough, by novel’s end, the not-so-aptly-christened Lucky—without a home now, without a tradition—has become the whale, as the whale seems to have become Lucky and, simultaneously, all the world’s malevolent economic forces, aimed at globalizing this fisherman into obscurity. Lucky works the bolt on his .416 Ruger and lets off a couple of hollowpoints. For his trouble he gets only grief.

Carpenter the poet has always been interested in myth. His 1992 collaboration with the artist Robert Shetterly, Speaking Fire at Stones, is preoccupied with those archetypal narratives that shadow our day-to-day existences. “Long ago, deep in his life somewhere, / it’s possible that a man blinded a raven,” the book begins obscurely. InThe Wooden Nickel, it’s a sight clearer just what myth we’re dealing with. Whales announce themselves more definitively than ravens, perhaps, but out on the water with Ronette and his Reba McEntire tape, it’s man against nature, man against woman, man against himself. It’s Carpenter versus Melville.

The book’s final scene, meanwhile, is wonderful and hopeful without being pat. But it is only just worth the journey. Well before the last chapter rolls around, Lucky’s character, with every rant all the more two-dimensional, has stalled out. It’s difficult enough that Carpenter should try to dramatize his opposite; then he makes the guy inarticulate about everything but carburetors and crustaceans. Could this—a stubborn novelist pushing himself against the limits of his form—be an instance of life imitating art?

CARPENTER THE EGALITARIAN

“The whole setting of boats and the sea, the impact of change on the coast: I wanted that to be felt viscerally,” Carpenter says. “And I specifically picked someone to write about who was limited verbally.” This is in marked contrast to Penguin, the protagonist of his 1994 debut A Keeper of Sheep, whose command of language was equal to her understanding of the world. Any story demands a storyteller who is articulate and insightful, who surprises readers rather than telling them what they already know. Carpenter admits that Lucky would need to feel things on another level. “I have a motto in writing,” he says. “Every insight or piece of understanding has to be visualized.”

In the end, argues Carpenter the egalitarian, all people are equally capable of understanding their own situations. They simply may not be able to say that in language. “That’s where symbolism comes in,” he adds. But according to the essayist William H. Gass: “Language, unlike any other medium, I think, is the very instrument and organ of the mind. It is not the representation of thought, as Plato believed, and hence only an inadequate copy; but it is thought itself.” Put another way, if Lucky Lunt, uneducated though he is, really can understand his own situation, then he must have words. Without words—well, in a novel especially, there’s nothing without words. If Lucky Lunt is to be our only porthole into the fictional world of Orphan Point, then he must have something more to say than the Japs are screwing him, every one of ’em.

In an interview last summer, Richard Russo talked about the problem he had writing his novel Nobody’s Fool, which was adapted into the 1994 film starring Paul Newman as the down-on-his-luck Sully. “The first draft I wrote in the first person from Sully’s point of view,” Russo said. “And Sully remained interesting throughout the book, but I was also very close to him. I realized that not allowing myself to get out of his consciousness was limiting the book. It was also making me irritated with the character.” Russo rewrote the book, opening up the point of view. In other words, he added an omniscient narrator. “We just need to go other places,” he said.

For his part, Carpenter maintains that “the drone of the middle-class, writerly consciousness just doesn’t interest me. I want my narration to get embedded into characters.”

So where can the novel’s insights—those little bursts of irony and understanding that we read for, that Russo is rightly famous for—come from?

“The reader has to make them,” he replies. “Simple as that. It’s like my teaching style. I’m much less of a lecturer and more discussion-oriented. Insight in a class of mine has to come from students. But what you do is you arrange stuff for them so that they’re forced to see certain things. That’s the challenge of a book like this.”

“Still,” Carpenter adds almost apologetically, “I’m always scared to let the reader out of my control.”

The same might be said for his characters.

Unquestionably, class dominates contemporary Maine literature more than any other theme. If The Wooden Nickel were set on Cape Cod instead of the Maine coast, it would still be a Maine novel, and an entertaining one at that. And William Carpenter’s contribution has amounted to a fascinating but ultimately failed experiment: Can we really understand the other side? Are we big enough, not just as readers but as writers, to challenge our own snobbery?

Lucky Lunt, for one, is not.

In talking about her Jewish employers, his daughter tries to explain her own family’s dire circumstances: “Don’t you see, Daddy, we don’t have customs. We live in a cultural vacuum. The Hummermans can’t watch any TV after sunset on Friday. It’s very refined.”

“Can’t be Friday,” he says, “you must of heard it wrong. Friday’s World Wrestling night on ESPN.”

The Wooden Nickel by William Carpenter (Little, Brown, 320 pages)

Maine Times, April 2002