APPEASING THE SPIRITS

Relatively unknown, even after 13 books, several of which have been acclaimed as masterpieces, Israeli writer Aharon Appelfeld has nonetheless led a remarkable life. Born in a small town in what is now the Ukraine, he watched as his mother, grandmother and scores of other Jews were murdered with pitchforks and kitchen knives by invading Nazis and Romanians. He and his father were put on a forced march that began with 200 people and ended with 30. Eventually, the young Appelfeld—he was barely nine at the time—escaped from the camp and joined the Soviet army as a kitchen boy. After the war, he immigrated to Palestine, where he began to write, often supported by only the anonymous contributions of friends.

In a hauntingly beautiful essay published in the Nov. 23rd New Yorker, Appelfeld writes about returning to the town of his birth after a half a century. At first he is reluctant. Some memories may be better left undisturbed; still, he confesses, “for years, the village lay within me.” So, with an Israeli television crew at his side, Appelfeld makes the journey back. When he arrives, he confronts local residents, asking them about the mass grave where his mother is buried. At first, they feign ignorance. Then, in a flash of guilt and frustration, they relent and point in its direction. “It seemed that, even though no Jews remained (there),” Appelfeld writes, “their spirits wandered about everywhere, and must be appeased.”

But those spirits do not only torment the Christian Ukrainians who have tried to forget the horrible atrocities of the Second Word War; they torment Appelfeld, too. He quotes Hebrew poet Saul Tchernikhovsky: “A person is only the ground of a small land. A person is only the outline of his native landscape.” For Appelfeld, coming home was finding that landscape, filling in that outline and, finally, appeasing the Jew inside of him.

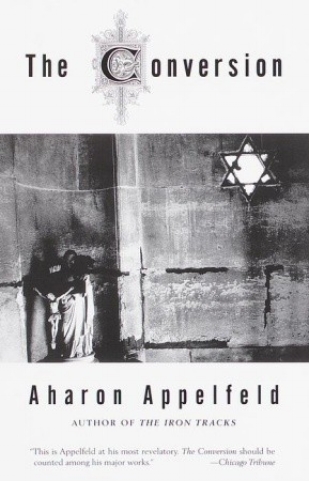

Something of the same dilemma faces the protagonist of Appelfeld’s new novel, The Conversion (translated into English by Jeffrey M. Green and published by Schocken). Karl Hubner, however, is a self-imposed exile. Living in Austria a generation before the Holocaust, he converts to Christianity not because he is persuaded by the arguments of the local priest, Father Merser, but purely for pragmatic reasons. It seems that his promotion to the prestigious post of municipal secretary would be impossible otherwise. The novel opens as Karl finishes the ceremony, only to be greeted with these strange words from a friend of his aunt, who has also converted: “‘We’re criminals,’ she leaned over and whispered. ‘Those who are dearest to us we neglect. In the world to come, they’ll whip us like dogs.’” Indeed, the remainder of this spare and often bitterly ironic novel serves as a troubling fulfillment of the old woman’s prophecy.

Karl’s promotion is nearly blocked by Hochhut, a successful entrepreneur and yet another convert, who has crusaded against the Jewish merchants in the town center. Once safely in his new post, Karl challenges Hochhut in an especially ferocious and, for him, politically damaging campaign to win compensation for the soon-to-be deposed merchants. Meanwhile, Karl initiates a secret relationship with his former nanny, Gloria, a woman almost two decades his senior. An uncomfortable feeling of incest stains the relationship. It is as if Karl, who continues to occupy the house of his deceased parents, were trying to reclaim something of his lost family and religion. Gloria, though, is a non-Jew who only plays the role of the good Jew, observing the holidays, even fasting when it is called for. Like the Biblical Ruth, she does this out of loyalty to the family that rescued her from poverty.

The Conversion layers irony upon irony. Conversion does not free Karl, as he expects, but steals something vital away from him—something he looks for in Gloria, something he travels to his parents’ native village to find. He languishes in a socio-religious no-man’s land, unobservant in two faiths, accepted by no one but Gloria. At the same time, for most of his countrymen, he will never be anything but a dirty Jew, deserving of nothing. Even as he fights the virulent anti-Semitism that surrounds him, he fails to fully confront his own, reluctant submission. At one point, Karl recalls the villagers who mourned for his mother’s passing: “We are Jews, and there is nothing to be ashamed of. And at the end of the mourning period, they cried out: The Jewish people lives! These were the wretched merchants of the center, whose sons and daughters had been ensnared by Father Merser’s wiles and had left their parents’ homes in disgust.”

The Holocaust hovers over The Conversion, casting its dark shadow on each line of Appelfeld’s rich, unsentimental prose. Karl searches madly for the Jewish spirits who taunt him, looking everywhere, it seems, but inside himself. Appelfeld, meanwhile, asks what it takes to appease those spirits and what is lost when they are abandoned. It is undeniably an unsettling novel, but The Conversion proves Appelfeld a master not just of the Jewish heart, but the human heart, as well, with all its terrible hungers and contradictions.

The Conversion by Aharon Appelfeld (Schocken, 240 pages)

Icon (Iowa City), December 1998